The Reformation of Greek Religion

Patriarchy defeated matriarchy; in a parallel development, transformed rites were substituted for human sacrifice. The first development finds expression is several mythologems: (VI.5) the mythologem of the dragon-slayer, Perseus and the Gorgon Medusa; (VI.7) the mythologem of rape, of Zeus and his many “loves”; and the summative (VI.8) mythologem of cosmological succession, in which the Olympians replace the Titans as rulers in heaven. The (VI.6) mythologem of the giants’ revolt records a late attempt by matriarchy to rebel against the authority of the rising patriarchy.

The iconography records that that the final victory of patriarchy occurred relatively late within the archaic period and continued to be accompanied by violence. The Lelantine War (c.734—c.680) began over a dispute between Chalcis and Eritrea in the island of Euboea over the use of the fertile Lelantine plain. It is said to have involved coalitions of all the Greek states, and to have coincided with the Spartan first war of conquest of Messenia (c.735—c.715). The violence continued. This is recorded in the imagery for the period, but that imagery also records the ongoing social prominence of women. Figurative representation had by this time returned to Greek art, but the greatest earliest exponents of the new forms, the Dipylon Master (active c.760—c.750) and the Hirschfeld Painter (active c.750—c.735) still give primacy in their paintings of funeral processions to a dead woman, a Queen or Priestess surely, mourned by countless female attendants, and buried in ceremonial pomp with processions of chariots and soldiers bearing traditional Mycenaean figure-of-eight shields that could hardly be of practical use in the era of hoplite warfare that deploys the round shield in mass formations. In other words, in the C8th female domination and social prestige had not yet been broken. The same conclusion arises from study of the icon of the seated female goddess—an age-old emblem of female authority that would eventually be usurped by Zeus—the statue of Zeus made by Phidias for the Temple of Zeus at Olympus (435) represented him enthroned, replacing by a god the place hitherto occupied by a goddess: men by that time had won. But by 700 they had not won—not yet.

The iconography records that that the final victory of patriarchy occurred relatively late within the archaic period and continued to be accompanied by violence. The Lelantine War (c.734—c.680) began over a dispute between Chalcis and Eritrea in the island of Euboea over the use of the fertile Lelantine plain. It is said to have involved coalitions of all the Greek states, and to have coincided with the Spartan first war of conquest of Messenia (c.735—c.715). The violence continued. This is recorded in the imagery for the period, but that imagery also records the ongoing social prominence of women. Figurative representation had by this time returned to Greek art, but the greatest earliest exponents of the new forms, the Dipylon Master (active c.760—c.750) and the Hirschfeld Painter (active c.750—c.735) still give primacy in their paintings of funeral processions to a dead woman, a Queen or Priestess surely, mourned by countless female attendants, and buried in ceremonial pomp with processions of chariots and soldiers bearing traditional Mycenaean figure-of-eight shields that could hardly be of practical use in the era of hoplite warfare that deploys the round shield in mass formations. In other words, in the C8th female domination and social prestige had not yet been broken. The same conclusion arises from study of the icon of the seated female goddess—an age-old emblem of female authority that would eventually be usurped by Zeus—the statue of Zeus made by Phidias for the Temple of Zeus at Olympus (435) represented him enthroned, replacing by a god the place hitherto occupied by a goddess: men by that time had won. But by 700 they had not won—not yet.

|

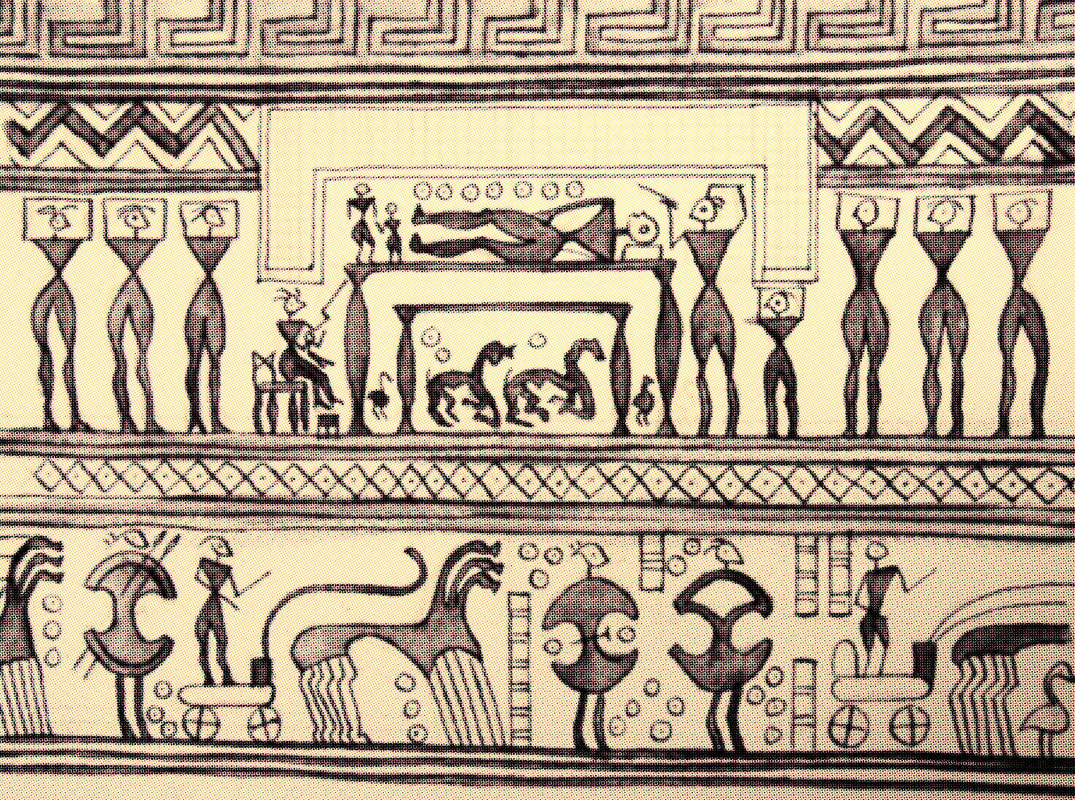

Krater, grave marker

Hirschfeld Painter, Metropolitan Museum, c.750—735 Depicted is a scene of lamentation for a deceased male figure. Figurative representation has returned, found in the interstices of the endless patterns of geometric art. The iconography of this scene is highly significant. The dead man is placed on an altar or bier. To the left we see figures of a woman and child. She holds in her arm a rod or sceptre, a symbol of authority. Her status is also shown by the fact that she sits on a chair or throne and has a footstool. We may infer that she officiates at the ritual lamentation, a clear indication of continuing female power in the priesthood. She may be the “wife”, but either she or another officiating woman appears to the right of the bier, also with a rod and accompanied by a child.

|

|

Apart from the deceased man and the child, whom we presume to be the male successor of the man, only women appear in the upper segment. The women are shown in the state of lamentation, by the icon of rending of the hair, a survival from Mycenaean times. Underneath the bier, there wild goats in mourning.

|

|

Therefore, nature also mourns the passing of the

hero. Hence, the man is an incarnation of the spiritus vegetativus or

akin to it. This is a fertility rite. Matriarchy has not yet been

overcome by patriarchy in the C8. The emblem of a swan appears several times (only shown twice in the illustration), indicative of a cult association. In the lower segment, men appear in procession paying their respects to the dead man. They bear figure-of-eight shields, emblematic of Mycenaean matriarchy, an indication of ceremonial, for they would have been useless in the context of contemporary Greek hoplite warfare. The Dipylon Master’s greatest work depicts a similar scene of lamentation, but for a dead “queen” rather than a “king”.

|

Monster-slaying is the content of the Perseus mythologem. A Corinthian pyxis (a cosmetic box, therefore part of the female toilette) from c.680—c.650 illustrates the “contradiction”. One side presents the traditional image of matriarchal dominance—the Goddess flanked by two winged griffins—the other shows Heracles fighting the triple-bodied monster of Geryon. The image of three bodies is a symbol of the Goddess, who manifests herself threefold, and thus the painter has unconsciously expressed his divided commitment to both ideologies—no contradiction in emotion—and logic had not yet been born. Greek mythology was born. By this, I mean that all those stories, myths, legends that we call “Greek mythology”—the stories about the gods and their loves, about the heroes and their struggles, and of the Trojan and Theban cycles, all those were laid down in this epoch. There is no evidence in the iconographic record that “Greek mythology” existed before this time—c.680 is almost the earliest date—and coincides with Hesiod (c.700) and Homer (c.669)—the conscious and deliberate fabricators and architects of Olympian religion, but not without the same contradiction as the painter—for Hesiod particularly loves the Goddess, and Homer is no stranger to her either, even if his Goddess is Athena, the transformed vision of female divinity within an ultimately masculine order.

|

An amphibious assault

Image from a middle geometric II skyphose, Eleusis, c.800—760 Imagery points to continuing conflict at the closure of the Dark Age (c.750). The ship is identified as belonging to the cult association identified by a swan, and the defenders use Mycenaean figure-of-eight shields. The reverse side of the skyphose depicts a battle with slain warriors.

A departure

Image from an Attic late geometric IIa krater found at Thebes, attributed to the sub-dipylon workshop, c.735 The image is reminiscent of the Warrior Vase, as a man “takes leave” of a woman as he departs on a large ship with two rows of oarsmen. The context is not necessarily war. The ongoing power of women is attested—the woman holds a circular object in her hand, surrounded by dots indicative of radiation; it is a symbol of power. On the prow (not shown above) is the symbol of a swan. The image also shows a figure-of-eight shield. Even on the boundary between the Dark and Archaic ages, men served the Goddess.

|

The traditional date for the institution of the Olympic Games (776) is a significant event on the boundary between the Dark Age and the Archaic Period. It marks a stage in the victory of men, because at these games only men compete, and symbolic of their male preserve, they compete naked to the exclusion of all women. Contrast that with the image from Knossos of the exclusively female audience of priestesses watching over dancing female nymphs and male bull-leapers and the imagery tells the whole story: what need is there of any argument? How can the fundamental pattern be opposed? How can its monumental significance be denied or ignored? When men meet in an exclusively masculine environment to complete, friendly and hostile rivalry is a stimulus to further development. They compare their local traditions, and (VI.10) genealogical mythology is born; (VI.11) the myths of collective actions both draw them together in one culture and emphasise their distinct contributions. We see the birth of the myths of Troy and the Theban wars. The watchword of male society is (VI.12) agon—strife, struggle, competition in athletics, culture and war. The favourite depictions of Greek art shall henceforth come to be exemplars of struggle (agony)—the battle of the Lapiths and Centaurs; the battle with the Giants, and the battle with the Amazons.

|

Myth of Perseus and Medusa

Schematic representation of the image circling the Eleusis amphora by the Polyphemos painter, active in Aegina or Athens. Eleusis Archaeological Museum, c.670—650 The artist is famous for his dramatic rendering of the blinding of the Cyclops Polyphemos by Odysseus and his men, painted onto the neck of this amphora. Part of the representation of the myth of Perseus is damaged and reconstructed above; we assume that Perseus decapitates Medusa with a sickle, as in the canonical myth. From left to right—Athena; Perseus; the head and wings of Medusa, an ambiguous symbol, possibly a tree or body part; vegetation; the body of Medusa; the two Gorgan sisters of Medusa, Stheno and Euryale fleeing. This image is of great significance in the history of Greek religion, marking pictorially the victory of patriarchy over matriarchy; it comes within the same decades as Homer’s final redaction of the Iliad (c.677). Commentators have observed that the artist, in his endeavour to picture what a Gorgon would look like, has shown their heads in the form of cauldrons, thus, unconsciously or otherwise, associating these monsters with cult and sacrifice. The myth is not yet fixed at this date, as Stheno and Euryale, the sister-Gorgans, were later to be identified as immortals—only Medusa, mortal, could be killed. Significant events at Athens must have taken place between 730 and 670, though the historical and legendary material for that period is scant. The reformation at Athens was cemented one hundred years’ later by the reforms of Epimenides conducted under the aegis of Solon (594), and during the era of Pisistratus (547—527), which was one of patriarchy and Olympian religion “full-steam ahead”.

|

The Reformation of Greek Religion resulted in not one but two religions coexisting usually in harmony, but sometimes not. Mycenaean-Minoan religion is a vegetation religion, whose central concern is the promulgation of the fecundity of nature, the growth of crops and all things; the Goddess is its chief deity, and she appears as one among many only because nature has so many facets, both as to purpose and as to place. It is pantheistic only in the sense that the Goddess is everywhere. Olympian religion is a religion of the High Father who administers Justice and Providence; he is the ultimate guardian of the moral law; his central concern is to direct fate and see that oath-breakers are punished. The breach of oath, rather than the kidnap of Helen, is the moral failing of the Trojans in Homer’s Iliad; the moral cause of their downfall. So, it is no accident that the idea of punishment in the afterlife appears as the (VI.13) mythologem of eternal punishment; at this stage, the concept of Hell as a place of damnation is born. There is no evidence for the existence of Hell in earlier Greek religion.

|

A komos

Icon from a column krater, from Kaza, Elefheres in the style of the Komast workshop, 580—570 Men, partly clothed, dance with naked women at a religious festival. The religion of fertility and the Goddess continued to be celebrated at all times of the ancient world, while the Olympian patriarchy was created as a superstructure.

|

While they engaged in extensive commerce, the ancient Greeks were predominantly agriculturalists; the bulk of their hoplite armies comprised yeomen farmers; at the upper end of the social ladder were aristocrats, who rented out land, or had the land cultivated on their behalf by a mixture of free and bound labour—the serfs in the Spartan state, called Helots, were no better than slaves. In other words, the primary concern of religion with nature could not be transmuted. Hence, Greek religion divided into two parts: firstly, there was the superstructure of the Olympian gods, the official rulers in heaven and administers of justice; they evolved into departmental gods and a pantheon was constructed. Secondly, the old fertility religion was reformed into a system of symbolic and transmuted rites. We call this Chthonic religion; it is a religion of the earth in which that which is buried and is reborn, as vegetation, is closely related to that which lives underground, the worship of ancestors and heroes, the realm of the dead, who could walk the earth as angry ghosts or be summoned. The distinction between Olympian and Chthonic religion is encapsulated in the differences of sacrificial ritual. In Olympian religion the animal victim, called an “offering”, is sacrificed with head pointing upwards upon a high altar to the gods; the sacrificial meal is divided between gods and men, with men gaining the better portions, and the feast is conceived of as a communal meal with the gods. In Chthonic religion the animal victim, called a “sacrifice”, is slain with head pointing downwards upon a low altar or directed towards a trench; the blood drains downwards and the offering is burnt as a holocaust—no part of the victim being consumed by the worshippers. By the classical age, Greeks pictured super-nature as divided between upper and lower realms; they worshipped and sacrificed to both.

The theme of transmuted sacrificial rites, and the abandonment of the obligation to provide a human victim, provides the substance of many a story from Greek letters. The plot is the same everywhere; so prevalent that it is impossible to deny that it records a historical process. We have (VI.14) the mythologem of substitution.

The theme of transmuted sacrificial rites, and the abandonment of the obligation to provide a human victim, provides the substance of many a story from Greek letters. The plot is the same everywhere; so prevalent that it is impossible to deny that it records a historical process. We have (VI.14) the mythologem of substitution.

|

The statues in the river at Potniai … they call the goddesses. … There is also a SHRINE OF DIONYSOS the Goat-shooter. They once got drunk at a sacrifice and committed the outrage of murdering Dionysos’s priest. They were immediately seized by plague, and the cure came from Delphi: to slaughter an adolescent boy to Dionysos. A few years afterwards they say the god substituted a sacred billy-goat to take the boy’s place. They show you a well at Potniai where they say the mares go raving mad when they drink the water (Boiotia, 9.8.1—2).

|

This material encodes mythic (iconic) and historical (semantic) content; the mythic aspects point to the original matriarchal layers, with the connection of Dionysos to the Goddess, and the emblem of Demeter, the mares; it also indicates the terror of the Bacchic frenzy. For a more developed variant of the same mixture of myth and history, we have the continuation of the rites of Triklarian Artemis:

|

This is how they say the human sacrifices to Artemis came to an end: Delphi had already sent a prophecy that a foreign king would come to their country with a foreign divinity, and stop the ritual sacrifice to Triklarian Artemis. When Troy fell and the Greeks divided the spoils, Eurypylos son of Euaimon received a chest with a statue of Dionysos in it; they say it was made by Hephaistos and the gift of Zeus to Dardanos. … So Eurypylos opened the chest and saw the statue, and as soon as he saw it he went out of his mind: that is, he was usually raving mad, but now and then he came to himself. Being in this condition he did not make the voyage to Thessaly, but to the gulf of Kirra, and he went up to Delphi to ask about his illness. They say the oracle told him that when he found the people offering a foreign sacrifice he should install the chest for worship and live there. The wind carried Eurypylos’s ships to the coast near Aroë; he landed there, and came on a boy and a virgin being taken to the altar of Triklarian Artemis. He could easily see this was the sacrifice, and the people of the district remembered this oracle, seeing a king they had never seen before and suspecting that he might have a god inside the chest. So Eurypylos got rid of his illness and the people got rid of their sacrifice, and the river got its modern name, Placation.

The title of the god inside the chest is the Overlord; his chief worshippers are nine men chosen freely by the people for their personal prestige, with the same number of women. On one night of the festival the priest carries out the chest: that is the privileged night, when the boys of the district go down to the river of Placation with wreaths of wheat-ears on their heads, the way they dressed them in antiquity to be taken to Artemis for sacrifice. (Achaia, 7.19.3—7.20.1) |

The religion of Dionysus had originally required the sacrifice of a human victim; but here it is reformed. This mythological history also contains the motif of madness that follows the opening of a chest containing a god or relic. (For example, we meet the same mythologem in the Athenian story of the daughters of Erecthonios.) The nature of the madness is unexplained in all cases; I suggest calling it “madness” is a later patriarchal and aetiological gloss on the rites of sacrifice and an allusion to Bacchic frenzy. Hence, the material above also records an example of (VI.15) the institution of the cult of a hero. This momentous religious development began from 850 onwards. The ideology may be reconstructed. The chest contains the remains of some dead hero, whom may be presumed to have been sacrificed in some earlier epoch; hence, the substitution of the remains of the chest for the rite of the sacrifice of a living victim. The throwing of effigies of men and animals into bonfires, graves or pits has a similar motive. The cause of the disturbance of the Dark Age was the demand for human blood within the context of matriarchal religion, and the refusal to meet that demand; human nature has found a way out by compromise—an earlier sacrificial-hero will suffice, and effigies may be substituted for persons. The institution of the hero-cult stimulated interest in the histories of the occupants of the Mycenaean tombs which housed their remains; questions were asked, and legends sprang up. In other words, it is a working hypothesis that the legendary material of the hero cycles was invented in the C8 in response to this demand. Working on fragments of oral tradition the earliest epic poets developed sagas of heroic exploits; Homer came a little later, and transformed two of the crude romances into great art and profound religion by combining that material with a Zeus-theology.

|

The wedding of Peleus and Thetis

Part of the icon from the Sophilos Dinos, a black-figured wine-bowl from Attica, c.580—570. Peleus welcomes his wedding guests—a procession of gods and goddesses. A work of monumental significance to the evolution of religion. Sophilos has written the names of the deities depicted, indicative of the fixing of the cannon of Olympian religion, for those who look upon the vase may not have known who the figures represent. Sophilos is teaching the Olympian religion. The iconography is also being fixed—for example, Iris as messenger carries a staff and points backwards in a gesture announcing the guests, and Dionysus carries a vine. The image of Dionysus is illustrative of the reformed conception of the sacrificial god-victim, now polite and respectable. In an act of unthinking masculinism, Sophilos has omitted to include the intended bride, Thetis, in the representation. He is the first artist to sign his work—the inscription under the portico of Peleus’s house reads, “Sophilos made me”.

From right to left the whole procession comprises: Iris, Demeter, Hestia, Chariklo, Leto, Dionysus, Hebe, Cheiron, Themis, Nymphs, Zeus and Hera, Graces, Poseidon and Amphitrite, Muses, Ares and Aphrodite, Apollo and Hermes, Moirai, Athena and Artemis, Oceanos and Thethys, Eileithyia, and finally Hephaestus. |

The motif of compromise between the two halves of the religion is also expressed in (VI.16) the mythologem of the divine marriage, the Heiros Gamos. This is a celebration of the sacred marriage of Zeus and Hera, that could be duplicated at the mortal level—one of the most popular themes of black-figure vase painting was the icon depicting the marriage of mortal hero, Peleus to immortal goddess Thetis, the mother and father of the demi-god Achilles. In a sense, every marriage is an instance of this divine marriage—an impulse to bring the two religions, of the matriarch and patriarch, together in harmony. Another instance of this mythologem is the marriage of Cadmus and Harmonia. This is a transformed mythologem of the original marriage or union of Dionysus (as Boy-God) to his mother, the Goddess.

The desire for harmony is as fundamental in human nature as the impulse to discord, but harmony is not always easy to achieve, and the substitution of one blood rite by another, or by a symbolic non-blood rite, does not remove the underlying motivation for sacrifice. Hence, in times of stress, the perceived need for sacrifice may re-surface, expressing itself even as a demand for a human victim as “more perfect”, and it is this which lends credence to those accounts in antiquity of the continuation of the rite at Rome, Athens and elsewhere. The “logic” that leads devout people to conclude that the gods demand a human victim is framed in that system of cognition that I have called primitive materialism. Hence, the resolution to the problem of human sacrifice, and of all sacrifice whatsoever, can come only with the end of that system. The rejection of the theoretical justification for sacrifice of any kind comes at the price of a new religion altogether. It was the Greeks who paved the way for this.

It seems that the Greeks became struck by the horror of human sacrifice and first felt the divine impulse to do away with it before any intellectual position against sacrifice was developed. But this impulse was first grasped by individuals, and the oral tradition records that the reformation was the work of inspired prophets, and that some of these men gave their lives in the service of humanity, for they were themselves sacrificial victims. However, in the material it is difficult to discern more than a trace of the historical personages.

(1) Orpheus is preeminent among these teachers and became the eponymous founder of the yet further reformation of Greek Religion that is known as Orphism, to which Pythagoras may be said to have been a follower. The religious significance of this second reformation, which owes nothing directly to any person of the name Orpheus, cannot be underestimated. (Important sources for the historical aspects attaching to the myth of Orpheus are Pausanias, Boiotia, 9.30.3—5, Diodorus 1.23, Conon, Narratives 45 and Ovid, Metamorphoses XI. 1—85.) Some points concerning the possible historical person of the Dark Ages, and his first reformation: (a) this movement is associated with the rejection of all blood-sacrifice whatsoever and vegetarianism. (b) The legends connect Orpheus with misogyny and patriarchy; he is said to have been dismembered precisely for his refusal to participate in the orgiastic rites of women, and in his violent death, we discern the fundamental mythologem of ritual human sacrifice as well as an act of revenge on the part of matriarchy against masculinism. (c) Orpheus is said to have advocated a form of monotheism in the worship solely of Apollo as the Sun. (d) Orpheus is said to have travelled to Egypt; this is another recurring motif in the legendary material relating to the reformers of Greek religion. This is credible as history, because it is generally accepted that Egypt first and for a long time alone in antiquity gave up the rite of human sacrifice; I suggest that this is in part the motive of the great praise heaped on Egyptian religion by commentators such as Herodotus and Diodorus. During this Dark Age we anticipate that as connections with the Levant and Egypt were re-established, Greek religious thinking was influenced by the ideas they found, and we also anticipate human vectors of such a development.

(2) The myth of Melampus, like that of Orpheus, is projected onto legendary time before the Trojan War; it is not difficult to show that any such projection results in internally inconsistent chronology and genealogy. The mythologems present in the Melampus material belong to the Dark Age. In them we see a strong trace of a real historic personage, a healer who instituted a reformation at Argos. (Important sources for the historical tradition are Pausanias, Corinth, 2.18.4, Herodotus, 2.49, Diodorus, IV.68.3 – 69.1 and Apollodorus, 1.102.) Some points: (a) The tradition reports that Melampus cured the madness of the women of Argos, who were instigated by Dionysus. As a result, Anaxagoras (“king of the market-place”), son of Megapenthes, made a three-fold division of the kingdom with Melampus and his brother Bias. It is fascinating, that through the linking motif of the name of Megapenthes, these events are located in the generation after those attached to Perseus, and I am reminded that in one tradition this is Megapenthe, a woman, not a man. By connecting the two stories, we have here an account that reads almost like a history of religious wars spread over two generations. In the first generation, female warriors supported by contingents drawn from the Aegean islands went on the rampage but were killed by Perseus and his men. There followed a separation of the kingdom between Mycenae (patriarchy) ruled by Perseus, and Tiryns (matriarchy) ruled by Megapenthe, a priestess. However, in the ensuing violence, Megapenthe killed Perseus and another violent insurrection of female warriors scourged the land. Melampus instituted the reformed rites of Dionysus, associated with phallus worship, and peace was concluded. (b) Herodotus also associates the reformed rites specifically with importation from Egypt and cites Cadmus of Tyre as the vector. In this, Cadmus is also becoming an important character who is assuming a historical presence belonging to the conclusion of the Dark Age. He is specifically cited by Diodorus as being the originator of the Phoenician alphabet; Diodorus attributes to Orpheus a “Phrygian poem” composed using “Pelasgic letters”. (He attributes the use of Pelasgic letters also to Linus and Pronapides, the “teacher” of Homer.) (c) Pausanias remarks, “The Argives are the only Greeks I know divided into three kingdoms.” Whenever we see the mention of a threefold division of power, we suspect the Dorian three-tribe structure, and this gives a hint that the civil war also involved conflict between Dorian and Achaean tribes. (d) The myth also records that Melampus secured his kingship by marriage to Iphianeira, the daughter of Megapenthes. This is an instance of the mythologem of matrilineal succession. The extract from Herodotus is so instructive that it merits full quotation.

The desire for harmony is as fundamental in human nature as the impulse to discord, but harmony is not always easy to achieve, and the substitution of one blood rite by another, or by a symbolic non-blood rite, does not remove the underlying motivation for sacrifice. Hence, in times of stress, the perceived need for sacrifice may re-surface, expressing itself even as a demand for a human victim as “more perfect”, and it is this which lends credence to those accounts in antiquity of the continuation of the rite at Rome, Athens and elsewhere. The “logic” that leads devout people to conclude that the gods demand a human victim is framed in that system of cognition that I have called primitive materialism. Hence, the resolution to the problem of human sacrifice, and of all sacrifice whatsoever, can come only with the end of that system. The rejection of the theoretical justification for sacrifice of any kind comes at the price of a new religion altogether. It was the Greeks who paved the way for this.

It seems that the Greeks became struck by the horror of human sacrifice and first felt the divine impulse to do away with it before any intellectual position against sacrifice was developed. But this impulse was first grasped by individuals, and the oral tradition records that the reformation was the work of inspired prophets, and that some of these men gave their lives in the service of humanity, for they were themselves sacrificial victims. However, in the material it is difficult to discern more than a trace of the historical personages.

(1) Orpheus is preeminent among these teachers and became the eponymous founder of the yet further reformation of Greek Religion that is known as Orphism, to which Pythagoras may be said to have been a follower. The religious significance of this second reformation, which owes nothing directly to any person of the name Orpheus, cannot be underestimated. (Important sources for the historical aspects attaching to the myth of Orpheus are Pausanias, Boiotia, 9.30.3—5, Diodorus 1.23, Conon, Narratives 45 and Ovid, Metamorphoses XI. 1—85.) Some points concerning the possible historical person of the Dark Ages, and his first reformation: (a) this movement is associated with the rejection of all blood-sacrifice whatsoever and vegetarianism. (b) The legends connect Orpheus with misogyny and patriarchy; he is said to have been dismembered precisely for his refusal to participate in the orgiastic rites of women, and in his violent death, we discern the fundamental mythologem of ritual human sacrifice as well as an act of revenge on the part of matriarchy against masculinism. (c) Orpheus is said to have advocated a form of monotheism in the worship solely of Apollo as the Sun. (d) Orpheus is said to have travelled to Egypt; this is another recurring motif in the legendary material relating to the reformers of Greek religion. This is credible as history, because it is generally accepted that Egypt first and for a long time alone in antiquity gave up the rite of human sacrifice; I suggest that this is in part the motive of the great praise heaped on Egyptian religion by commentators such as Herodotus and Diodorus. During this Dark Age we anticipate that as connections with the Levant and Egypt were re-established, Greek religious thinking was influenced by the ideas they found, and we also anticipate human vectors of such a development.

(2) The myth of Melampus, like that of Orpheus, is projected onto legendary time before the Trojan War; it is not difficult to show that any such projection results in internally inconsistent chronology and genealogy. The mythologems present in the Melampus material belong to the Dark Age. In them we see a strong trace of a real historic personage, a healer who instituted a reformation at Argos. (Important sources for the historical tradition are Pausanias, Corinth, 2.18.4, Herodotus, 2.49, Diodorus, IV.68.3 – 69.1 and Apollodorus, 1.102.) Some points: (a) The tradition reports that Melampus cured the madness of the women of Argos, who were instigated by Dionysus. As a result, Anaxagoras (“king of the market-place”), son of Megapenthes, made a three-fold division of the kingdom with Melampus and his brother Bias. It is fascinating, that through the linking motif of the name of Megapenthes, these events are located in the generation after those attached to Perseus, and I am reminded that in one tradition this is Megapenthe, a woman, not a man. By connecting the two stories, we have here an account that reads almost like a history of religious wars spread over two generations. In the first generation, female warriors supported by contingents drawn from the Aegean islands went on the rampage but were killed by Perseus and his men. There followed a separation of the kingdom between Mycenae (patriarchy) ruled by Perseus, and Tiryns (matriarchy) ruled by Megapenthe, a priestess. However, in the ensuing violence, Megapenthe killed Perseus and another violent insurrection of female warriors scourged the land. Melampus instituted the reformed rites of Dionysus, associated with phallus worship, and peace was concluded. (b) Herodotus also associates the reformed rites specifically with importation from Egypt and cites Cadmus of Tyre as the vector. In this, Cadmus is also becoming an important character who is assuming a historical presence belonging to the conclusion of the Dark Age. He is specifically cited by Diodorus as being the originator of the Phoenician alphabet; Diodorus attributes to Orpheus a “Phrygian poem” composed using “Pelasgic letters”. (He attributes the use of Pelasgic letters also to Linus and Pronapides, the “teacher” of Homer.) (c) Pausanias remarks, “The Argives are the only Greeks I know divided into three kingdoms.” Whenever we see the mention of a threefold division of power, we suspect the Dorian three-tribe structure, and this gives a hint that the civil war also involved conflict between Dorian and Achaean tribes. (d) The myth also records that Melampus secured his kingship by marriage to Iphianeira, the daughter of Megapenthes. This is an instance of the mythologem of matrilineal succession. The extract from Herodotus is so instructive that it merits full quotation.

|

2.48: In other ways the Egyptian method of celebrating the festival of Dionysus is much the same as the Greek, except that the Egyptians have no choric dance. Instead of the phallus they have puppets, about eighteen inches high; the genitals of these figures are made almost as big as the rest of their bodies, and they are pulled up and down by strings as the women carry them round the villages.

2.49. Now I have an idea that Melampus the son of Amythaon knew all about this ceremony; for it was he who introduced the name of Dionysus into Greece, together with the sacrifice in his honour and the phallic procession. He did not, however, fully comprehend the doctrine, or communicate it in its entirety; its more perfect development was the work of later teachers. Nevertheless it was Melampus who introduced the phallic procession, and from Melampus the Greeks learned the rites which they now perform. Melampus, in my view, was an able man who acquired the art of divination and brought into Greece, with little change, a number of things which he had learned in Egypt, and amongst them the worship of Dionysus. I will never admit that the similar ceremonies performed in Greece and Egypt are the result of mere coincidence—had that been so, Greek rites would have been more Greek in character and less recent in origin. Nor will I allow that the Egyptians ever took over from Greece either this custom or any other. Probably Melampus got his knowledge of the worship of Dionysus through Cadmus of Tyre and the people who came with him from Phoenicia to the country now called Boeotia. The names of nearly all the gods came to Greece from Egypt. |

In these extracts, Herodotus has dropped his ethnographic approach of reporting only what people say, and is speaking on his own account. The only error of Greek scholars in relation to this and other material is to attribute all such material to the pre-Trojan epoch rather than to the boundary between the Dark Age and Archaic period, c.750, when the Greeks were learning to write using Phoenician script. That almost universal error in dating is even challenged by Herodotus in this very passage, when he writes, “Greek rites would have been more Greek in character and less recent in origin.”

I must emphasise the role of methodology in all of this interpretation. I do not claim to “know” that any of the above material is historical, or that if it is, to be able ascribe to it an absolute date; I let the fuzzy logic and the mythologems do the work. These mythologems belong to the conclusion of the Dark Age—for they spell the end of that darkness by the institution of reformed rites and belong to the period when writing is being learned. As such the material contains the important (VI.17) mythologem of the Egyptian origin of the reformed religion of Dionysus and attaches to that the motif of the human vectors: Cadmus, Orpheus and Melampus.

Fundamental to the transformed rites is the substitution of puppets, figurines and symbolic rites, blood and non-blood, for human sacrifice. The fertility religion of the goddess most certainly encouraged copulation; here we see that an actual practice of fecundation of the priestesses is replaced by a phallic procession. It seems in the legend of Melampus that the people as a whole solved the problem, and there is a hint that this resolution took place at a public assembly held in the market place—the agora, presided over by a president—Anaxagoras.

(3) In Musaeus, Linus, Olen, Manto and Mopsus we have other potentially legendary and/or near-historic figures associated with the reformation, but the information is scant.

(4) Hesiod is no mere shadow and an important figure of the reformation. His Theogony represents an important statement in the history of religion; it would be wrong to see it as built on too long a tradition. Material in it is likely to have been imported from neo-Hittite sources, but its novelty should not be overlooked either, for the mythologems are transformed. He is the author of the mythologem of cosmological succession. It is really his invention and marks the new phase of Greek religion. By this cosmology the Greeks most definitely understood that their religion had been reformed, and that the older and more barbaric rites that formerly they had practised, represented by the order of the Titans are replaced by the civilised rituals of the Olympians. It was for this reason that when Greeks discussed the religion of other nations, they did not hesitate to ascribe to them worship of Cronos where they saw barbarism. A passage in which Diodorus attributes the sacrifice at Carthage of the “noblest of their sons” to Cronos has already been quoted. The same applies to their discussion of Tryian Melqart, whom they connected with Heracles. (They were not alone—coins issued by Hannibal during the second Punic war bore the inscription “Hercules-Melqart”.) But the Greeks were keen to distance their Heracles from the Phoenician one, who, connected to Cronos and identified with Hebrew Moloch, was a Canaanite god associated with child sacrifice. The whole of Hesiod’s Theogony proclaims to the Greek world, “We do not do this anymore”. But, like other reformers, Hesiod is said to have met a violent death, recorded by Thucydides (3.36.9) and Pausanias (Boiotia, 9.35.5).

I must emphasise the role of methodology in all of this interpretation. I do not claim to “know” that any of the above material is historical, or that if it is, to be able ascribe to it an absolute date; I let the fuzzy logic and the mythologems do the work. These mythologems belong to the conclusion of the Dark Age—for they spell the end of that darkness by the institution of reformed rites and belong to the period when writing is being learned. As such the material contains the important (VI.17) mythologem of the Egyptian origin of the reformed religion of Dionysus and attaches to that the motif of the human vectors: Cadmus, Orpheus and Melampus.

Fundamental to the transformed rites is the substitution of puppets, figurines and symbolic rites, blood and non-blood, for human sacrifice. The fertility religion of the goddess most certainly encouraged copulation; here we see that an actual practice of fecundation of the priestesses is replaced by a phallic procession. It seems in the legend of Melampus that the people as a whole solved the problem, and there is a hint that this resolution took place at a public assembly held in the market place—the agora, presided over by a president—Anaxagoras.

(3) In Musaeus, Linus, Olen, Manto and Mopsus we have other potentially legendary and/or near-historic figures associated with the reformation, but the information is scant.

(4) Hesiod is no mere shadow and an important figure of the reformation. His Theogony represents an important statement in the history of religion; it would be wrong to see it as built on too long a tradition. Material in it is likely to have been imported from neo-Hittite sources, but its novelty should not be overlooked either, for the mythologems are transformed. He is the author of the mythologem of cosmological succession. It is really his invention and marks the new phase of Greek religion. By this cosmology the Greeks most definitely understood that their religion had been reformed, and that the older and more barbaric rites that formerly they had practised, represented by the order of the Titans are replaced by the civilised rituals of the Olympians. It was for this reason that when Greeks discussed the religion of other nations, they did not hesitate to ascribe to them worship of Cronos where they saw barbarism. A passage in which Diodorus attributes the sacrifice at Carthage of the “noblest of their sons” to Cronos has already been quoted. The same applies to their discussion of Tryian Melqart, whom they connected with Heracles. (They were not alone—coins issued by Hannibal during the second Punic war bore the inscription “Hercules-Melqart”.) But the Greeks were keen to distance their Heracles from the Phoenician one, who, connected to Cronos and identified with Hebrew Moloch, was a Canaanite god associated with child sacrifice. The whole of Hesiod’s Theogony proclaims to the Greek world, “We do not do this anymore”. But, like other reformers, Hesiod is said to have met a violent death, recorded by Thucydides (3.36.9) and Pausanias (Boiotia, 9.35.5).

|

Sphinx

The crowning ornament of the east pediment of the Treasury of the Siphnians at Delphi, before 524. In this icon the feminine character of the Sphinx has been suppressed—she is depicted without breasts. The Sphinx is emblematical of the ambivalent feelings of both ancients and moderns to feminine power. The Goddess has both a benign and terrible aspect—as Queen of Heaven she is the bringer of fertility and all good things—as Queen of the Underworld, she is the bringer of death, destruction and sacrifice. Reviled as the author of riddles in the myth of Oedipus, she ever retains her charisma, mysterious and worshipful.

Mother enthroned with child

Boetian terracotta figurine, c.450—440 |

(5) Another reformer was Epimenides of Crete. The legendary material concerning him I shall omit, but there is a detail of considerable historical significance recorded by Plutarch in his Life of Solon. In the preliminary, Plutarch tells the story of the sacrilege committed by Megacles, one of the family of the Alcmaeonids, against the supporters of Cylon during an attempted coup. These men were ritual supplicants at the shrine of the Furies on the Acropolis, when they were stoned to death and otherwise killed by Megacles and other archons. This incident is the source of the legend of the curse of the Alcmaeonids, which reverberated all the way through Athenian history. Archaeologists think they have found the mass grave of these men; the bare skulls seem still to cry out in utter pain. As the event was called a crime, and the throwing of any man into a pit or slaying in the Acropolis must be thought by some as favoured by the gods, this is an archaeological find that merits discussion under the heading “sacrifice”. But this story is in itself an aetiological wrapper for events taking place at Athens that have even wider religious signification.

|

In this situation they [the Athenians] sent to Crete for Epimenides of Phaestus … He made the Athenians more punctilious in their religious worship and more restrained in their rites of mourning; he did this by immediately introducing certain sacrifices into their funeral ceremonies and by abolishing the harsh and barbaric practices in which Athenian women had indulged up to that time. But his greatest service, which he achieved by various rites of atonement and purification and by erecting places of worship, was to sanctify and consecrate the city and make people more amenable to justice and better disposed to live in harmony with one another (Solon, 12).

|

From Thucydides (1.126) we know that the purification also involved the digging up and expulsion of the corpses of the Alcmaeonid family. The economic, social and political aspects of Solon’s reforms have been much discussed; what has been omitted is their religious dimension—which is social too, in that this purification represents a definite limitation of female rights and rites. One would like to know for certain to what is meant by the phrase “harsh and barbaric practices” that are attributed to the Athenian women; there is a definite anti-feminist tone in the account offered by Plutarch.

Left: Kouros

Meranda, c.530

Meranda, c.530

The kouroi represent the triumph of unabashed masculinism over matriarchy.